(Editor’s note: This is the first of two Q&A sessions with Dr. James Klotter, a historian from Kentucky.)

By NKyTribune columnist Steve Flairty

Perhaps feeling a little more self-assured than I deserved after selling my first book in 2005, I reached out to Dr. James Klotter, a well-known individual who shared my enthusiasm for our state, and asked him for a HUGE favor.

He certainly didn’t know me from Adam, but I dared to ask if we might get together and discuss something I vaguely remember as specific Kentuckians from the past that merited being the subject of biographies. We met at the Joseph-Beth Booksellers coffee shop in Lexington after he quickly agreed to my request. Although he was an excellent listener, I mostly simply let him ramble so that I could feel energized. I was a little anxious but also excited.

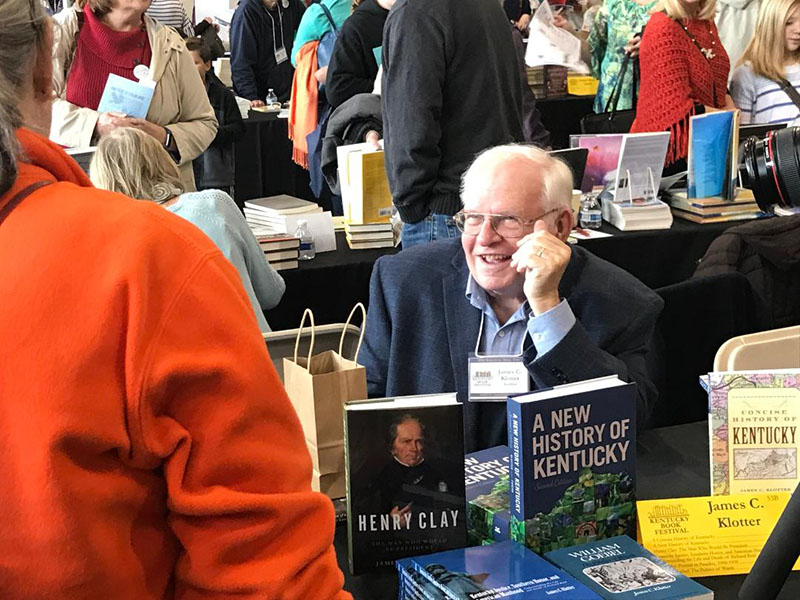

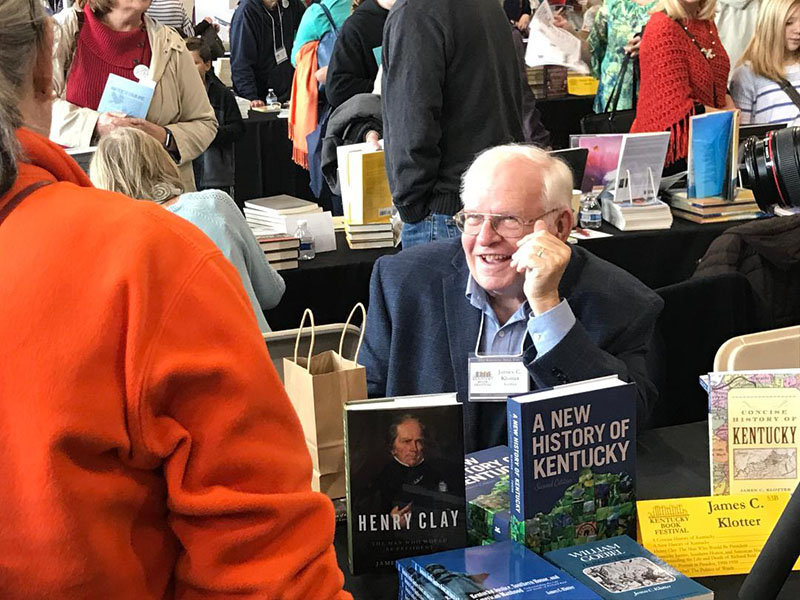

Due to his extensive knowledge and his modest, gentlemanly demeanor, I was thrilled to get the opportunity to interview Dr. Klotter, the State Historian and member of the Kentucky Writers Hall of Fame, by email for this column twenty years later. He has the receipts to verify that he is a treasure of Kentucky. His accomplishments include speaking to groups on Kentucky history around the state, writing several articles, publishing at least eleven books, and serving as the Executive Director of the Kentucky Historical Society.

The purpose of the questions for Dr. Klotter is to offer a well-researched, reliable viewpoint on Kentucky’s history that could help lead the Commonwealth to even greater success in the future.

Flairty: What are the most significant lessons you’ve learned from your extensive experience studying, teaching, and writing about our state? In what ways do you think those lessons should guide Kentucky’s future choices?

Klotter I’ve discovered, among other things, how little I know about the history of the state and how significant it is. One does not visit a doctor without a personal history, just as one does not visit a tax accountant without past financial records. As a people, why should we be any different? We must re-learn everything, making the same mistakes and learning nothing if we are unaware of our past.

On the other hand, we can emulate the good deeds of our predecessors if we have some knowledge of the commonwealth’s past. Perhaps, for instance, we can observe how leaders seized opportunities in spite of the criticism and left a better state, as was the case when Governor Bert Combs issued a contentious executive order to grant black citizens more rights or when Governor Martha Layne Collins brought Toyota to the state. The state played a crucial leadership role in both cases, one that all citizens ought to imitate. History is important.

Flairty: It’s clear to you how important it is to teach our kids about their Kentucky roots. Faces of Kentucky, your elementary school textbook co-written with your wife, Freda, is a gem and, in my opinion, also very helpful for people seeking a basic understanding of the Commonwealth’s history. What recommendations do you support to assist the state do a better job of educating our young people about Kentucky?

Klotter We appreciate your positive remarks regarding Faces of Kentucky. Just as Freda authored the majority of the outstanding Teachers Guide, which was also published by the University Press of Kentucky, I wrote the majority of the text. This is a fantastic illustration of how state institutions may collaborate for the commonwealth’s benefit.

Along with Henry Clay, A New History of Kentucky, and my novels Kentucky Justice, Southern Honor, and American Manhood, I rank that work as one of my best works. I created Faces to close a gap in the literature at the time—that is, books authored by authors with some knowledge of state history. Because many of the textbooks dealt with generalizations and preconceptions about the commonwealth in a cookie-cutter manner. I remember one that had a lengthy section on canals with pictures that suspiciously resembled the New York Erie Canal.

Unfortunately, Kentucky history has been deemphasized; it was a full course in the seventh or eighth grade when I was a child, but it is now emphasized in the fourth grade (at least that’s when I last looked) and is supposedly integrated in the other grades. However, with a focus on the fourth grade, the subject shifts to Daniel Boone, Henry Clay (maybe), Abraham Lincoln, and a study of the composition of government, with little to no mention of events that occurred after the Civil War or how the state’s economy changed over time. Since Kentucky history is not taught as a stand-alone subject, there is no established curriculum and the requirements are ambiguous and disjointed. According to Scott Alvey of the Kentucky Historical Society, this means that our state’s history is presented as tales or vignettes during several years of social studies instruction, leaving it up to the teachers to weave into the greater national narrative.

Although it is imperative that elementary-aged students have access to history, older pupils are better prepared for the depth and nuance that come with comprehending Kentucky’s rich past. Some states offer two comprehensive courses on their state’s history; Kentucky need to have at least one, ideally at a non-elementary level, so that all kids are aware of the positive and negative influences that have influenced them.

Furthermore, putting a thorough Kentucky history course later in a student’s academic journey brings the material closer to the point where the student will be able to vote and engage in community activities as an adult. According to Wendell Berry:

If they have never heard each other’s stories or have forgotten them, how can they know each other? How can they tell if they trust each other if they don’t know each other’s backstories? In addition to not helping one another, those who don’t trust one another also dread one another.

We can evaluate information thanks to history. Which do we prefer—frightened, untrusting, and uneducated grownups, or trusting, inquisitive, and knowledgeable ones?

Flairty: In order to rank our best presidents, scholars have frequently convened. Would you mind trying to list the best governors of Kentucky? I’ll let you provide the standards by which you will judge.

Klotter: It’s not as easy as it seems. Why? Since every governor has different conditions, the most effective governor may be one who manages to accomplish goals despite a lack of funding or a legislature that is fiercely opposed. But I’ll concentrate on real achievements for the sake of this question. Even though the 19th century had some powerful governors, governance was far easier at that time. The governor didn’t have much to do in the beginning, so he didn’t even live in the capital city full-time! Furthermore, the state had fewer than 100 employees as late as 1900.

In actuality, the modern governorship didn’t start until after World War II and the Earle Clements administration. Bert Combs (1959–63) had the best administration of all his successors, in large part because of a sales tax that was passed by the electorate. For instance, he created parks and parkways, KET, a community college system, a reward system for state employees, and an executive order that increased the rights of the state’s Black inhabitants. And all of that throughout a single term without any major controversies.

After Combs, there were four consecutive successful governors: Ned Breathitt, Louie Nunn, Wendell Ford, Martha Layne Collins, Paul Patton, and others.

By the way, Joseph Desha (1824–28) was probably the worst governor. He caused a conflict that nearly wrecked the legal system and sparked a civil war along party lines during his reign, damaged Transylvania, one of the top colleges in the country at the time, and then shamefully pardoned his own son after he was found guilty of murder.